6/4/18

It’s no wonder the body is central to so many Indian practices. Today we had several unique experiences that made me very conscious of my body. The first of these was a meditation session that lasted approximately 30 minutes. While relaxing, I couldn’t help but giggle inside at the fact that the meditation guide created his own meditation CD, complete with echo voice effects; it reminded me of a cheap sci-fi from the 60s. However, the experience was quite interesting. Our meditation instructor reminded us that the body only uses 1/3 of its lung capacity on an average day, but through meditative breathing, one can learn to become one with the self entirely. He instructed us to deep breath through our noses, first long, then medium, and then short, in counts of ten. He noted that if we began to feel lightheaded, this was our brain being oxygenated to its fullest extent, it was our bodies becoming conscious of our brains. Our instructor lead us through a number of exercises wherein we consciously made an effort to relax the left side of our bodies, section at a time, and then the right side of our bodies. Fully relaxed, we concentrated on breathing in the positive and breathing out the negative. Overall, the meditation was a practice in patience, as I kept thinking about when it would end; despite the great deal of relaxation it provided me, I couldn’t help but think about the giggling professor beside me and the way I needed to incorporate the meditation into my coursework for Bodies and Embodiment.

The second experience was not necessarily a momentary event, rather it was a daylong struggle. The heat today was intense. It didn’t just toast the skin, but it threatened to consume you; as you stepped into the street, it was like stepping into the mouth of a dragon. Step out of a conditioned building and into the air and you are literally enveloped by a wave of heat, although it doesn’t feel like a wave, it feels like being submerged in a just-roasted-marshmallow. It’s a sticky heat that has no escape. It enters your lungs, threatening to suffocate you. It fills your hair, making it stand on end, frizzy with moisture and sweat. It forces your body to drop moisture, not little beads of perspiration, but giant boulders of moisture rolling down your face, neck, and back. I am not sure I have felt a heat like this before. It makes one tired almost immediately, and thankful that I left the make-up off for the day—my face would have melted off in seconds. I did, however, enjoy the heat more so than the frigid air of the AIIS building—while inside, I kept thinking, “I can’t concentrate on anything said during lecture, because I keep thinking about how cold I am.” Outside, however, I had to fully concentrate on my body…”Is it overheating? Should I be drinking more water? Am I going to pass out? Is this sweat ever going to stop? Is the sweat under my clothes, soaking through, making my body visible to the passerby?”

6/5/18

My bodily experience for the day: my stomach is telling me something, and I think it’s “Stop while you still have the chance!” I have been eating the most wonderfully rich and spicy curries the last two days. The first arrived as our “boxed” lunch from AIIS yesterday—inside were lentils, spicy slaw, and paneer tikka masala. The lunch came complete with roti, some pickled vegetables, and a plain yogurt. For dessert, there was a dough ball soaked in rose syrup—not my cup of tea. I wanted to finish everything but the dessert, lick the little curry compartments and stuff the rest of the roti into the back of my throat, but it was all too much. Instead, I started with my plain yogurt, ate all of my lentils and spicy slaw, had a few bites of paneer and roti, and taste-tested the dessert. Still, this was quite a bit of food, so I went to bed without dinner. Tonight I have done the same. The group went for lunch together in Defense Colony Market; we stopped at a vegetarian restaurant, which claimed to serve some of the best Southern Indian Style food. It was here that I ordered Mysore Paneer Dosa, another spicy little dish that burned going down and continues to wreak havoc on my stomach. How can I say “no” to curry, though, when it begs to be eaten for breakfast, lunch, and dinner? My stomach says “no,” but my mind keeps saying, “yes, try that one.” All day long I have felt my body try to reject my food choices. My bowels are on strike, and my stomach is paying the price for culinary pleasure in Delhi. Although I do not have Delhi belly, I can feel the bubbles build up in my stomach; they start weak, barely noticeable, and expand upward, making a show of their strength and persistence. I push them down, but they refuse to go unnoticed. These are the times one is reminded of the stomach’s strength, as well as its susceptibility to small shifts in climate. It is just another effect of India’s ability to make one aware of their body.

Co-existence is the word shared by many guest lecturers over the last two days. Co-existence and contradiction. India is a nation of complexity; it is vibrant, dynamic, and complicatingly diverse. According to Dr. Mishra, India embraces the new while maintaining a connection to tradition. With over 500 cultural communities and 4500 castes, India can be defined not as one identity, but as a multitude of identities. It is a country where binaries exist, but more-so, they co-exist. What this means is that binaries such as old/new take on new meaning, such that each is valued for what it brings to the table, although one (i.e., the new) may represent progress for certain sects of society (i.e., government). While the people of India live by tradition, the old, there is a constant push for change, the new—change in policy toward lower and Other Backward castes, change in treatment of women, change in response toward Pakistan. Time in India is conceptualized as linear, yet this linearity is superimposed on a concept of cyclical time structures. Hijras are a remnant of the past that are newly claiming LGBTQ rights. Indians are resourceful. Yesterday on our bus ride back to the hotel, we passed many well-groomed parks and many highway shanti-towns—some literally sitting on top of highway/freeway medians. It was mind-boggling to consider this contradiction in sight: great poverty and great beauty within feet of one another, a times within each other. There were people sleeping under bridges, nay, living under bridges. Not like the transient folks in the United States, with their cardboard boxes as mattresses and backpacks with whatever remnants of their lives they could carry, some even with bikes and pets. The people sleeping under bridges here in India were nearly nude, nearly starved, and as I imagined, with nowhere to go, possibly no energy to go.

6/7/18

I was so exhausted yesterday that I couldn’t keep my eyes open past 5:30 when we returned from the Indian National Museum. Most other people in the Fulbright group had a difficult time sleeping; not I. Although, oddly enough, the few people with whom I spoke from the group also had strange dreams, dreams that involved loss and/or challenging familial situations. Andrea dreamed about her lost dog, Darlene about her lost grandson, and I about my lost sister. Sarah had gone off to visit a friend without ever having told my mother and I where exactly she had gone. When the electricity went out in the neighborhood, we knew we had to go get Sarah, but from where we did not know. I spent hours trying to find her, luckily I finally did. It was not a sad dream, at least. Given that I rarely dream so vividly, and wake up to remember these dreams, it was surprising to remember this one and to hear that others similarly dreamt vividly. Perhaps it is the heat that is invading our dream worlds?

I cannot recall a time that I have sweat so much. I didn’t sweat this profusely in Marrakesh three years ago, nor in the Cayman Islands mid-July of last year. Randi invited me on an adventure to find Sangat, a social justice organization in India that works towards women’s rights.

We arrived just on time, having taken two separate subway lines and walked through a beautiful park, semi-sketchy (but perhaps upper-caste) neighborhood, and several urine scented allies. (side note: the first train we did not realize was mixed-gender until I felt this sudden urge to crawl out of my skin. Every sense was telling me that this 98% male filled subway car could spell disaster for me and my body. I was hyper-aware of the stares, of the bodies close to mine, of the possibility of terrible things happening, simply for presenting as feminine, foreign, and maybe even queer. Yet, we survived the trip and eagerly hopped into an all female car on the next line—a much quieter, less tense experience that had my mind dancing with relief).

Upon arrival, 11:00 AM on-the-dot, we signed in at the front desk in the open-air carport and were escorted up to the first floor. Nastasia and her colleague (did she give her name?) introduced themselves while Randi set herself up for note taking and video recording and I tried to wipe the waterfall of sweat from my face. The torrential sweat embarrassed me to the point of having to excuse myself to the bathroom.

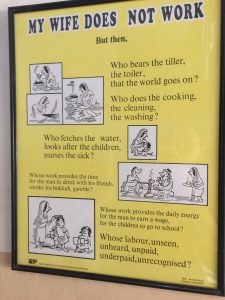

Polluted/ing bodies. With so much resting on the caste system, it has been interesting to learn about the complications of viewing various bodies as pure and impure. On the one hand, Dr. Mahalakshmi described a potentially holistic version of the caste system, perhaps one that existed pre-colonization: Varnasramadharma is a “way of righteous living” that is conceptualized as a fully body, face as the Brahmin caste (knowledge producers), arms as the Kshatriya caste (protectors), thighs as the Vaisya caste (laborers), and feet as the Shudra caste (servers). In this case, all parts of the body work together to achieve social functionality. Alternatively, and perhaps as a consequence of British colonialism, the caste system serves to differentiate each body part within a hierarchy, such that the head will never touch the feet, and the feet are conceptualized as merely a tool (a “cog in the wheel” of the machine?) for getting the head/mind what it needs. Interestingly, the caste system emerged in this way during the 6thcentury, also a time when mind/body dualism gained traction in other Western countries. There must be some connection here. By the 4thcentury BCE, the caste system became rigid and was supported by patriarchy, a system meant to control women’s bodies. This control is clearly visible in India today. When you walk in public, it feels as though 90% of the Indian population is male. When we asked Nastasia, of Sangat, where all the women are, she noted that they are in private spaces, because public spaces are still dangerous for women—sexual harassment is rampant, and women’s mobility is policed by the government and family…even the education system polices women’s bodies with set curfews (6-7:00 PM for “their safety”) and paternalistic leadership that ensures women are not meeting the wrong caste of men (i.e., “Romeo Patrols”).

The only women who can “afford” to exist in public are those who are already viewed as polluted…the dalit or “broken/scattered” untouchables. These are also the women who face the most violence, oppression, and abuse. What of trans and hijra women, though? They are often relegated to the borderlands of acceptability due to their gender presentation, as well as their sex work (which is often a consequence of their borderland positionality). Do these women, who presumably work in public, also get policed in the same way as other Indian women, or are they policed differently due to their identities? It seems they are policed differently:

6/10/18

I nearly had heatstroke yesterday as we spent the morning toasting under the Indian sun. It is not as though we sunbathed near a fountain or tried to experiment with how long our bodies could resist the temperature, but it is nearly impossible to escape the heat. It follows you, envelops you, refusing to let go. It fills your nostrils; I imagine this is what it must feel like to drown in a pool of hot whole milk. I did not have heatstroke, although at a certain point around noon, having walked through the Qutab Minar and Humayun’s Tomb over a few hours, I felt my body weaken and my mind become fuzzy. I immediately thought, “this is where I faint and am rushed to the hospital in India.” I did not faint, though, and made it on to the air conditioned bus along with everybody else in the group. I thanked my lucky stars to have the privilege of a tour bus with air conditioning. It still shocks me that people can live in such heat with so little water, food, and shelter. I feel for the poverty-stricken of India and wish there were something I could do to make their lives easier, more enjoyable, or perhaps even less painful. Am I projecting my fears onto their bodies?

Today was much more bearable, perhaps because we had a sand/rain storm yesterday around 5:30pm. I woke from a nap and noticed that it was pitch-black outside. “How strange,” I thought, “how could it be dark so early?” I quickly realized that the trees were blowing sideways and plastic grocery bags were flying past the window. It was a sandstorm that darkened the sky for a good 15-30 minutes, and along with the sand came the rain.

The rain cooled the atmosphere quite a bit, it cleared the plants of dust for the moment. When the rain stopped, the Fulbright group, myself included, took a cab to the Delhi Dance Academy where we learned three Indian dances—one Bollywood, one with sticks (Dandiya), and one Punjabi (Bhangra, perhaps). I thought I would be stressed trying to dance in front of a group of my peers, but it turns out that most of us were nervous, most of us were underprepared, and we all had a lovely time. There was no way to know that Bollywood dance requires so much energy; it looks fun on TV, but the steps are quick and there are many. Will I try Bollywood dance again, probably not, but I felt inspired enough to purchase the material for a sari today. Wearing a sari during our dance class was refreshing and it was relatively easy to put on/take off. Now if only I could figure out how the women get their sari tops made from the extra material provided.

6/11/18

Food is a major component of many different cultures. Growing up as a Catholic Chicana I can recall spending a good portion of lent giving up sweets and meats. We would avoid meat on Fridays and sweets throughout the 40 days of lent. It always felt like eternity. The various food taboos and practices of abstinence in India are intensely different from my own experience. Here, you have the history of Mughal (Muslim) influence, so pork is not really even considered consumable throughout India. Cows are considered sacred by some, making their consumption a non-issue. In terms of food purity for Hindus, the most polluting of foods (tamacic) are root vegetables, followed by grains (rajacic), leaving milk, fruit, and nuts/seeds/legumes for the purest (sattvic). What this purity/pollution scale does in terms of peoples is further enforces the difference in caste system, such that those who eat polluting foods are often those who are of the lowest caste, who then are not allowed to cook for those of the highest caste—the purity of the kitchen symbolizes the purity of the home. To further complicate matters, Jains do not eat anything that is living or has the potential for life. Their diet is strictly vegetarian, with the added exclusion of potatoes, garlic, and onions. But wait, plants are alive! However, Jains believe that the various forms of life exist within a hierarchy, based on sense perception. Thus, plants are acceptable to eat because they only have one sense, whereas animals have four or five senses (i.e., sight, smell, hearing, etc.). The overall goal for Jains is to be the least destructive to one’s environment, to commit the least amount of pain to all things around, including micro-organisms—it has been noted by an instructor that Jains will not walk after rainfall because they fear killing insects that have fallen in rain puddles. I wonder about the levels of guilt in the Jain community—if they accidentally kill a bug while walking, do they feel guilty or do they consider this a reality of human existence for which they must atone?

Transportation is a little challenging in Delhi. It is plentiful, yet requires some research and haggling. The subway goes all over the city and is air conditioned (halleluiah!). It is inexpensive, by our “outsider” standards, to get most places—from New Delhi, where we are staying, to Old Delhi the cost is approximately 40-60 rupees. The first day that Randi and I set off to Sangat (near Malviya Nagar stop) and returned to AUD (near Kashmiri Gate stop), we spent a good 20 minutes on the subway. Our journey to Sangat was initially anxiety producing, as we were probably two among 50 men in one subway car—the horror movies running through my mind were plenty. We realized quickly that there was a “Women’s Only” car at the front of the subway. This car was quiet, we received fewer stares, and it was generally more enjoyable. The motorized rickshaws are another option for transportation. They, too, are relatively inexpensive, although I suppose only the top 10% in India would use these—the other 90% make approximately 4000 rupees a year and would therefore not splurge on this form of transportation. These taxis remind me of Coco Taxis in Cuba; they are quick, they are plentiful, they only seat three (or four, if double-seated) semi-comfortably. The pedal rickshaws are also plentiful, although not for those in a hurry, and only seat two. We have been told that pedal rickshaw drivers typically come from rural areas to make survival money.

Given that the rickshaw economy is one of survival and the supply is way too high, you are expected to bargain your price before you get on the rickshaw. The drivers are all men, they are all darker skinned (perhaps from being in the sun and/or being of lower caste), and they are all quite thin—I have seen some that are emaciated and ragged. These men work hard when given the opportunity, and because the demand is so low, they often fight to get your bid.

Smells. Indian smells are unique to the region. In Delhi, the smells are pungent. Yesterday I purchased a masala lemon soda, out of curiosity. I realized that the masala flavor of this soda was exactly the smell I had experienced emanating from people’s sweat. Body odor is a common phenomenon in hot, humid places. Masala body odor is something else. Like the masala soda from which I kept taking small sips, even though I wasn’t particularly drawn to the flavor, the body odors in India both make my stomach turn and make my nose do a double-take. My visceral reaction is one of abject attraction.

I thought about this contradiction long and hard a couple days ago when I had walked into the guest bathrooms at Humayun’s Tomb. It smelled so strongly of urine that I could hardly think straight—or maybe this was compounded by the near-heatstroke. Rather than close my nose, though, I kept smelling this putrid urine smell, thinking how bad it was. I then got to thinking about how sanitized my living has become in the United States. I have water and electricity to clean my home, to flush my toilet, to wash my clothes. I have deodorant and sprays to remove odors from my things, my body. I do not have a relationship with the smells around me, rather a relationship with the non-smells around me. Perhaps this also contributes to the pure/impure binary that is so problematic in terms of differentiating good from bad forms of being and embodiment in the United States and beyond? Another smell that is quite common and equally abject is that of moth balls. What a disgusting smell, one to which I do not have an abject attraction. The building in which our classroom sits is shared by all on the floor, it has a single toilet and urinal, gets blistering hot by mid-day, and has loads of moth balls in both the urinal and sink. I try hard to stay hydrated enough to feel good during the days we are there, and dehydrated enough to avoid having to use the bathroom. It’s a delicate balance. I’ve also smelled the moth ball scent on people and in places, likely used to prevent moths from eating their clothing. This all comes from a place of great privilege, but I say, “let them eat cloth!”

6/15/18

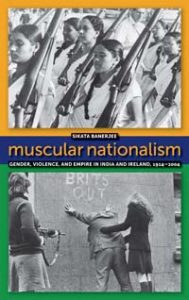

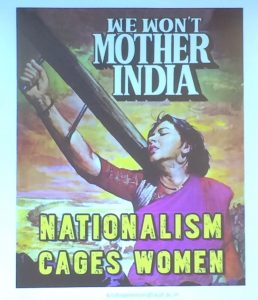

“The figures of Shanti, Bharati, Vivekananda’s women, and the culture [sic] of icons of warrior goddesses, indicate that, in the relationship between nation as woman and women in nation, the female body can take on traits of hegemonic masculinity in muscular nationalism, but these female bodies are at all times situated in a dynamic juxtaposition with competing imaginings of frail mother and chaste wife. Muscular nationalism is troubled by politicized femininity in its myriad forms and attempts to contain it through an emphasis on chastity. Female agency is further complicated by social anxiety around female sexuality.”-Banerjee, 2012, p. 68-69

It has been a long couple of days. On the 13thwe made it in to Amritsar, after having had the previous night to explore Khan market (an upscale market that felt a lot like the Chinese alley markets, but dirtier and smellier) with a small group of Fulbrighters. Amritsar feels significantly different from Delhi, partly related to the increase in temperature and a decrease in humidity, but mostly related to the people. Amritsar has a high population of Sikhs and this population resembles middle easterners (tall, thin, lighter eyes) more so than Indians (short, thin, dark eyes)—likely because of the close proximity to Pakistan, which was actually a part of India before Partition. Also, Sikh mustaches and beards are unmistakable. This morning when Randi, Andrea, and I went to the Golden Temple for sunrise, Andrea found a book on Sikhism that noted the “most manly” of all Sikhs is he who has a proud mustache and beard. Masculinity is alive and well in Northern India. But so is the movement toward gender equality.

This evening we attended the official border ceremony near Amritsar. I had watched videos of this ceremony before, but had not realized the extent of the performance. Essentially, armed guards on both sides of the India/Pakistan border perform a nationalistic, and thus patriarchal, ritual that involves marching and posturing—literally with arms flexed and peacock-looking hats flicked in defiance of the “other’s” similar show of might—on each side of the border. They are separated by elaborately decorated gates (the one on Pakistan’s side a bit taller, prompting me to wonder whether it was built second) with stadium seating on both sides. The Indian side has quite a bit more seating space than the Pakistan side, yet both draw crowds on a nightly basis (two on Sunday).

On the Indian side of the border, there is a male MC who riles the crowds, encouraging them to cheer and chant. He runs up and down the corridor between stadium seats, saying things that I do not understand, but imagine to be about the greatness of India, as the crowd chants “Hin-du-stan.” Women line up in droves to get the opportunity to run in a group of approximately eight, carrying large Indian national flags as people cheer them on. There is a dance party for women. The music is festive and the women look to be having fun; a few of our group attempted to join, but were turned away, presumably because men were not allowed on the “dance floor.” Had there not been military personel (two who looked like special forces), a border wall, and guard dogs (i.e., german shephards), I’d likely see this celebration as an Indian version of the 4thof July celebrations across the U.S. Reflecting on this event a day later, though, I think about the strange reality of this event—a nightly festival to celebrate the division of a formerly unified land and people. Even more strange is the fact that people travel from miles away (on the Indian side, at least) to participate; we sat behind a group of four young Chinese women and near another group of eight European (Spanish?) young women and men who looked like they had missed the boat to Ibiza. Further, it seemed as though the Indian participants were from other areas of the country; they were not the Sikhs we saw at the Golden Temple, at least. The show has either become (or always was) a tourist destination, complete with VIP seating (for which we did not pay, but were apparently White enough to pass) and popcorn and ice cream. The only thing missing was the souvenir shop.

On the Indian side of the border, there is a male MC who riles the crowds, encouraging them to cheer and chant. He runs up and down the corridor between stadium seats, saying things that I do not understand, but imagine to be about the greatness of India, as the crowd chants “Hin-du-stan.” Women line up in droves to get the opportunity to run in a group of approximately eight, carrying large Indian national flags as people cheer them on. There is a dance party for women. The music is festive and the women look to be having fun; a few of our group attempted to join, but were turned away, presumably because men were not allowed on the “dance floor.” Had there not been military personel (two who looked like special forces), a border wall, and guard dogs (i.e., german shephards), I’d likely see this celebration as an Indian version of the 4thof July celebrations across the U.S. Reflecting on this event a day later, though, I think about the strange reality of this event—a nightly festival to celebrate the division of a formerly unified land and people. Even more strange is the fact that people travel from miles away (on the Indian side, at least) to participate; we sat behind a group of four young Chinese women and near another group of eight European (Spanish?) young women and men who looked like they had missed the boat to Ibiza. Further, it seemed as though the Indian participants were from other areas of the country; they were not the Sikhs we saw at the Golden Temple, at least. The show has either become (or always was) a tourist destination, complete with VIP seating (for which we did not pay, but were apparently White enough to pass) and popcorn and ice cream. The only thing missing was the souvenir shop.

Since I am reflecting back on strange occurrences, let me go back a couple of days to the first time I was asked to take a picture with a couple of Indian children, which turned into a mob of Indian children, women, and young men. After leaving the beautiful, but steamy packed Golden Temple, our group entered the Jallianwala Bagh massacre site, the place where the British Colonel Dyer ordered his army to shoot unarmed civilians who were gathering to protest the deportation of two national leaders, killing anywhere from 379 to 1000 (the numbers differ because some statistics come from the British, while others come from the community). The Fulbright group had dispersed to explore the site and I found myself strolling through the memorial alone—something I had attempted to avoid at all other sites. Having turned a corner in the garden, I was tapped on the arm by the little hands belonging to a young boy, probably age eight or so. He was holding his younger brothers hand, and both seemed to want to practice speaking English with me. The older brother introduced himself, asked how I was and where I was from; I thought it was incredibly cute. I didn’t realize he had arrived with a massive crowd. Having had a small conversation with the brothers, they asked if they could take a picture with me: flood gates open. I am certain there are at least fifty pictures of myself with Indian women and children floating around India by this point—I made a point to limit my participation to the women and children. What a strange experience to have people desire to have a picture with you because of your whiteness. I had been making fun of the whiter folks in the group the previous week each time they were asked for a photo, knowing full well that I too look white to some, but not thinking that my time would also come. I suppose, as Ali noted, that this is the price (a very small one) that white-skinned folks must pay…it is a price that is far different than that paid by dark-skinned folks in white parts of the world. I do wonder if this is somewhat how people in human zoos felt, objectified merely for looking different. Still, I am thankful the objectification has not been accompanied with violence, which reminds me that white privilege, even for those of us who pass, is real.

6/16/18

I visit the Golden Temple twice. The first visit was rushed, as we were escorted in as a group, pushed through the main temple, then moved right along to the Jallianwalah Bagh site. Entering the temple was a bit anxiety producing for me. First and foremost, we were required to take our shoes off and walk around the temple barefoot—I have this thing about walking barefoot, a remnant of my college freshman fear of getting athletes foot from the shared dorm showers. We removed our shoes, gave them to the attendant in exchange for a metal tag at one of the numbered windows along the outside wall, and walked along the marble entryway until we reached the entry. To add to my anxiety, we were required to walk through an ankle-deep water bath prior to walking up a small set of stairs and into the temple; I could imagine the germs floating around the pool, waiting to attach to my feet. I quickly forgot about the germs as I entered the temple and saw the opulence of the structure inside. A golden temple connected by a long open-air corridor along the pond drew my eye. With the mid-day sun beating down on us, it was difficult to concentrate, but with that sort of golden luster, the eyes are constantly pulled back to the beauty of the temple. Compounding this effect was the chanting added to a beautiful tune, no doubt a song for the Sikh god. We learned that the chanting would continue for 18 hours of each day and that the temple is open to any and all at all times. Without an entrance fee, this sort of space is ideal for meditation and general relaxation; however, dawn is best. I invited any others from the group to join me again at the temple the following morning at 5 AM.

My hope was to see the sunrise over the temple rooftop—a plan foiled by the ever-present smog/fog/dust. The temple was quite lovely without the hustle and bustle of mid-day worship. It was still very busy, perhaps even more so at that time, yet it was cooler (maybe in the 80s) and more relaxing. People no doubt had slept at the temple, as there were bodies strewn about the temple, young, old, all genders and differing abilities. The music was more mellow, but no less beautiful. In retrospect, I wish I had felt more comfortable about sitting there for an hour or so alone, but I kept having this dialogue in my head about whether people would ask for more pictures with me—it bothered me enough to prevent me from taking the time to spend time in silence.

6/17/18

“All Indians are minorities”-Dr. Kumari

A few things that I have not had the energy to write about, but are very important to consider, are the religions of India. When Dr. Kumari noted during one of our AIIS presentations that all Indians are minorities, he was painting a picture of diversity in languages spoken, religions practiced, ethnic identities defined, and relationships built across geographies. He further explained that despite the great diversity in people, India was unified under a concept of “one India.”

This concept is difficult for me to define, particularly because of the diversity in religion and the ways in which religion permeates everyday life. Here is my understanding of the dominant religion in India: Hinduism. Hinduism is both a religion and way of life—a “way of righteous living,” which involves many different versions of caste and thus many different versions of embodying Hinduism. What makes Hindusim so interesting, though, is that it has no historical founder (i.e., Jesus or Mohammed), no fixed canon (although the Vedas are texts, they are not used as scripture), no monastic organization (i.e., sectarian temples and untrained Brahmin, not universal and official), no formal procedure of conversion (i.e., born Hindu), and is organized via caste. The guiding principle behind Hinduism is Varnasrama Dharma; it involves conceptualizing the various castes within the society as parts of a properly functioning body, such that the face or mind/knowledge represents the Brahmanas, the arms or protectors represent the Kshatriyas, the thighs (stomach, in some stories) or traders/laborers represent the Vaisyas, and the feet or servants represent the Sudras. According to the dominant (although by no means only) text on the Hindu “path,” the Rig Veda, all humans have a mixture of sattva (purity), rajas (passion), and tamas (inertia); the Brahmanas are thought to have more sattva, Kshatriyas more rajas, Vaisyas more tamas, and Sudras very little of all three qualities, and thus their duty to serve. In the Rig Veda, all parts of this “body” work together to accomplish social cohesion and health; two or more in opposition to or competition with one another will cause an ailing body. The contemporary hierarchy within this caste system, however, is said to have emerged from greed and perhaps even colonization—the British enforced a pronounced hierarchy between castes in their effort to exert and keep control over the larger Indian population as they enforced a moral code designating Sudras (a majority of the Indian population) as dirty and disposable, and the upper-castes as morally superior and worthy of British acknowledgment. How, then, did the emphasis on purity come to be? I’m not sure I have the resources to answer this, but I do know that purity is a major emphasis that has a strong influence on foods eaten by the various castes, as well as partner selection, and other relationship guidelines. In terms of foods eaten, Brahmanas may only eat food prepared by other “pure” castes—as one of our lecturers notes, “the purity of the kitchen symbolizes the purity of the home.” Only the “untouchables” eat cow, because their purity is not at risk. Indeed, only the lowest caste women are allowed to access public spaces to sell the leftovers from slaughterhouses, also making these women most at risk for public abuse. Notions of purity also work themselves into relationships between castes—Brahmanas only marry other Brahmanas; the “Anti-Romeo Squad” is a group of men who work to ensure that young women do not fall for a man in the “wrong” caste, and schools police relationships via paternalism (i.e., women only curfews and principal guardianship of female students). To say that the caste system in India is hierarchical and to paint this picture of unity in privilege/oppression via caste hierarchy would be a major mistake, though. Caste exists, but it exists in hundreds of different forms. According to Dr. Dash, this simplification of the Indian caste system is a form of Orientalism that takes the varna or textual analysis as literal, completely ignoring the jati or contextual realities of caste in India. A non-orientalist understanding of caste requires that one view them as independent and interdependent, as theorized and embodied, as both the one and the “Other.” Through a process of sanskritization, the dominant castes dominate in their local hierarchies—in other words, the Brahmanas are not always dominant. Further, caste relations are constantly shifting thanks to Dalit movements and groups, like the Dalit Panthers, who work to challenge and subvert the many forms of caste oppression in India.

Muslims and Sikhs may be the second and third largest religious groups in India, or I may only have them listed as such because of my visit to Amritsar, where there is a very obvious divide between the two. Muslims have a long history of rule in India, beginning with the Ghaznavid Dynasty in the North and ending with the Mughal empire through most of India, before the British gained power and then divided Hindus and Muslims in order to conquer (also see: Partition). The Mughals offered security to Hindus as their rulers, but could neither convert them nor do away with them—there were too many and their beliefs/practices differed too greatly (i.e., Muslims were monotheistic and Hindus polytheistic). Although Muslims ruled during the Mughal empire, their influence in Indian culture seems to end with the following cultural artifacts: the dome, written history (i.e., texts), the wheel, manuscript illustrations, and strong oral culture. Sufi shrines still exist—we visit one today, only to be turned away at the door for being women, a polluting force if not properly purified, we were told—although most Indian Muslims are Sunni and moved or were displaced to Pakistan after Partition. Side note: Sufism is interesting because its roots are in pantheism (i.e., seeing God manifest in many parts of the universe) and love; a reunion with God is possible through ritual (i.e., music and dance) and love. Sikhism, on the other hand, began in the 15thCentury, and is therefore a relatively new religion. It began with the birth of Guru Nanak (1496-1539) and is about “equality and justice for all”—a “brotherhood of man.” The text may be read by any gender and is based on a notion of “miri piri” or a balance of the worldly and spiritual. The goal for Sikhs is to live life to its fullest (loving, living, creating), while working toward spiritual growth via meditation on God and the spread of dharma and truth (i.e., being an “activist saint,” fighting oppression). The Sikh god is formless, secular, and imminent, while the individual is defined as simple, spontaneous, logical, fearless, and courageous (these last characteristics were likely included during the 5thGuru’s—Arjan Dev Ji—influence, after he militarized the Sikhs by creating a Khalsa or “saint-soldier” identity). Sikhs usually wear the following five items: uncut hair, a wooden comb, and iron bracelet, a dagger, and a special undergarment.

Buddhism and Jainism are two other religions practiced in India. Interestingly, Buddhism has its birth in India, yet did not survive long. It is egalitarian and tolerant, spread with minimal coercion, and did not seek to displace local religions—indeed, is incorporated in “high Hindusim” (i.e., non-sacrifice of animals and importance of fate or Karma). Buddhists believe that suffering is inevitable and that there are three main components of this suffering: sorrow, the cause of sorrow, and the cessation of sorrow. Although Buddhism did not survive India, it helped strengthen the difference in castes via the notion that people are born into a caste due to the good/bad karma from a previous life and were thus deserving of their status and position in this life. I know even less about Jains, except for the fact that they value all things that have the potential for life and therefore will take all necessary precautions to prevent the death of living creatures (see my previous note on Jains and their eating habits).

On a completely different note, I am almost out of PeptoBismol and I’m not sure my bowels can handle a day without the pink gold. I have not had one day here that has felt normal—is it the spice, the minerals in the water, the heat, or any combination of these? Also, are my teeth staining yellow from all of the curry? I noticed the other day that I was making myself sick by my own curry sweat smell.

6/19/18

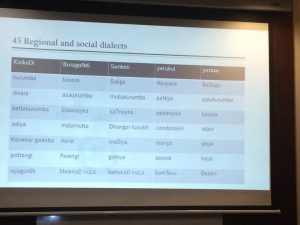

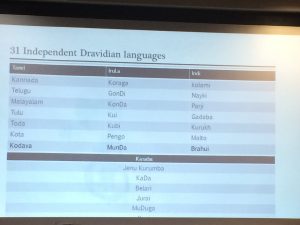

What is in a language? Everything. I typically teach the importance of language in each of my courses. Being a post-structuralist, a follower of Derrida (Derridian?), I recognize the contradictions in claiming this importance, all while trying to disclaim the importance—what is “queer” after all but a signifier of many other signifiers? Queer as identity, as community, however, can mean the difference between life and death for some. To study language in India, thus, has been a real treat. My initial fear was that I would learn all of these words that were important for communication in India, but which would really not help me get by in the way I would desire—to learn more about how non-academics live. And I have—learned some Hindi and Urdu words—but most of our language lessons have actually focused on the politics of language, on identity, and on identity politics. This is my academic heaven! I have learned that India has a very complex and interesting relationship with language. Given its cultural diversity, it is no wonder that it also has linguistic diversity. However, this diversity is complicated in a way that cannot compare to other countries I have visited (as a tourist or academic). For instance, India has 22 official languages that are represented throughout its 29 states, and over 1600 independent languages spoken overall. Most uniquely, state lines have been drawn in India based on dominant languages spoken in each area. In the North, Indo-Aryan based languages prevail, as do Astro-Asiatic and Sino-Tibetan based languages in the North East (by Tibet). In the South, Dravidian based languages prevail. In South India, alone, 76 different languages are spoken, 31 of which are independent, with 45 different dialects. Despite this diversity, by 2050 approximately 100 indigenous languages in India will die without many having been recorded. Consequently, cultures, identities, practices will die along with these languages, either being replaced by Hindi and English, or simply fading away—the sad part to me is in learning that many of these lost languages will likely be those that conceptualize people in communal (i.e., “we”) rather than individualistic (i.e., “I”) terms…there is something lovely about speaking to communal needs, although I recognize the consequences this may have in terms of individual identities. In India, language is important, but differently important because the caste system and thus social status, opportunities, and resources are intimately tied to it. Although most people in rural spaces may speak up to four different languages (i.e., their tribal, town/city, state, and Hindi language), there is a general expectation that people who use specific types of language (i.e., Hindi and English) are those from higher castes, while those who use more “tribal” languages are from lower or non-specified castes. As such, language differences are not celebrated by government officials as a point of pride, but as a problem that needs to be controlled—the government has sought to do so via the reduction of benefits for indigenous language speakers on employment tests and the New Education Policy (NEP) which promotes Hindi as a national language. Further, the Indian government has set up this paradoxical situation wherein they have given states the right to determine their own languages, while promoting Hindi as a national language, and also giving children and parents the right to choose their language of education—logically children and parents would choose English or Hindi, because this is the language of affluence and opportunity. So, is language important in India? Yes! Is there a solution to the language “problem”? I’m not sure. Morocco had to have an indigenous movement in order for the nation to officially recognize Amazigh languages; this was one language among two predominant languages, Darija and French—thank you colonizers (*insert sarcasm*). Still, the Moroccan government has difficulty enforcing the rule that requires institutions, like schools and businesses, recognize Amazigh as a legitimate language for commerce and communication. Imagine this situation, multiply it by 11, and you have the Indian situation, except with an added layer of caste. I tried to imagine the U.S. government redrawing the lines between states to fit dialects…where would my family go? My grandmother speaks Spanish fluently, but not official Spanish from Spain, nor from Mexico, but from New Mexico, a mixture of Spanish, English, and maybe even indigenous languages from the region. My mom speaks some Spanish fluently, but my siblings and I do not. Would my family have to choose separate states, or is it enough that we all use some Spanglish? Would our state be called “Spanglish,” while others were called “Kinda Canadian,” or “Cajun”? Would indigenous groups regain some of their stolen land, or would they lose more because their mother tongues were stripped from them? Would Ebonics be used to further marginalize specific minority populations, or could it empower them? Would Spanglish and Ebonics speakers be grouped closer together in the South, while the Almost Canadian speakers took the North? Now that I think about these dynamics a bit more, I see that some of us already code-switch, because we have had to learn how to use “proper English” to gain access to knowledge and resources. On a micro level, minorities in the U.S. share this in common with indigenous speakers in India, but on a macro level, our stories are very different. Understanding the macro-politics of language is important because those who control language can control people. Languages can both empower and disempower, they can draw people together and push them apart, they can create a national identity and construct national divisions. Language helps us communicate and yet it prevents us from communicating in other important ways (i.e., via action, practice, interaction).

6/22/18

We made it to Agra! I overheard somebody say that Agra is approximately two degrees hotter today than yesterday; at a certain point, two degrees extra in the scortching heat is like water in a bucket, although I wish I were sitting in that bucket. The body begins to sweat the moment it meets the outside air, which is more stifling than in Delhi—indeed, I am wishing for Delhi weather today. I drink water like it is going out of style, like I will never feel moisture coat my dry mouth and throat again. One bottle, two bottles, three. A peer noted at the beginning of this trip to India that they felt bad about all the plastic bottles we accumulated from all of our purified water consumption; I also feel bad, but not bad enough to quit my habit and risk the burden of too many amoebas in my tummy from a drink of tap water. I also feel bad about the damage we must be doing to the environment with our persistant use of the air conditioners in our rooms—a 65 degree room cannot be easy to maintain in 110 degree weather. I’m even afraid to leave my hotel room door open for too long, lest my precious cool air try to escape as the heat forces its way in to my space. Agra is still lovely, despite the heat. I don’t mind the profuse sweating, but I certainly will not miss burning my feet on various temple floors…if there ever were fungi to fear, I’m sure they burned to a crisp at the opulent temple we visit on our second stop in Agra.

I’ve wanted to touch on a few things mentioned by previous guest speakers while I still have them fresh in my mind. One of these things that boggles my mind is the conflict in India over cows. Understandably, we have seen more cows roaming the streets and tied in groups near trees in Agra than in Delhi. Agra appears much more agrictulrally based, but from what I can tell is still very mixed in regard to Hindi/Muslim practices (we even visit a Hare Krishna temple on our first day in Agra). One of the biggest conflicts between Hindus and Muslims seems to be over the use of cows—Muslims eat and use cow for leather, whereas Hindus see the cow as a sacred representation, of what, I haven’t quite been able to figure out. Thus, what we have learned from various academics and the daily newspaper is that cows are being used as a scapegoat (scapecow?) for Hindu/Muslim violence. Several Muslim men have been murdered across India for being accused of slaughtering cows—even if the accusation proves false.

To me, this is akin to the witch trials that occurred in the early U.S., although much less gendered and sexualized. I do wonder how a group gathers the support to actually beat and kill others who are simply accused of cow slaughter—it seems there are underlaying anxieties and fears related to nationalism or even masculinity? Speaking of nationalism, a recent Supreme Court order made it mandatory to stand for the national anthem during movie previews…weird! Also, Hindu nationalists have responded to the Adivasi community’s existence by making claims that it needs to bring the Adivasi into modernity in order to “help” them—I wonder how similar/different this is to the “civilizing mission” of the Western Europeans in the Americas. I do know that the caste system complicates this process, as the Brahmin are known to civilize, yet the Adivasi do not fit within the caste system because Hindus cannot convert them.

The Azad foundation is 10 years old and works to empower women through various community programs, but specifically through teaching them to drive and take up non-traditional livelihoods (NTLs) such as taxi driving. One of the most fascinating stories of empowerment told by the program administrators was one in which one of their driving students won a case in court which allowed her to drive a public bus in Delhi. While she won the case, she encountered many other issues around driving the bus (i.e., the uniform was not made for a woman’s curves, the bus had a driver’s seat that was not adjustable, and night routes were not practical nor safe). Each issue that the bus driver encountered highlighted the very real consequences of living in a patriarchal society which is not required to consider the various needs of those assigned female at birth. The Azad Foundation, however, fought hard with this bus driver to ensure that she started her first day at work as prepared to succeed as her peers. Beyond this, the foundation coordinates groups for men to learn about privilege and oppression so that they may also learn how to support and encourage women in their empowerment. Although the foundation does not directly support trans women, they do have trans participants in Kolkata—their biggest challenge is addressing the specific needs of trans women, which requires that the foundation do a bit more research into this area. Ultimately, though, the foundation teaches women their legal rights, how to negotiate boundaries, how to see their surroundings, and how to claim their own space in the public arena. These are all things that help the women survive as they enter male-dominant spaces.

One of our literature lecturers noted that India does not have many science fiction authors because “Indian culture does not work through a sense of the rational.” They look back through history, but more specifically through folk and mythology to understand their lives, rather than rationalizing their lives based on the present or future goals. I have to consider this a little more closely before I figure out what this may mean for other parts of Indian life.